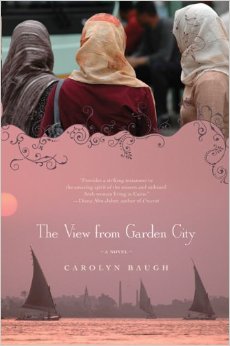

Carolyn Baugh, a native of Indiana who is in her fourth year of the Ph.D. program in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations at the University of Pennsylvania, writes in her new book The View from Garden City (Macmillan) about an unnamed American woman studying at the American University in Cairo who engages with several of Cairo’s women, learning more about their heartbreaking, fascinating and inspiring stories. As Publishers Weekly describes, “The American student’s Arabic professor, Afkar, who teaches her the delights of a precise cup of Turkish coffee, was forced into marriage with a weak, abusive man after an indiscreet crush as a girl. Huda, now perilously in her early 20s, loves penniless Sharif, but marries a financially stable man she finds physically repulsive, and learns to live with this decision. Huda’s mother, Karima, a childhood victim of female genital mutilation, marries the grocer and faces a horrific birth control situation. And the American learns the stories of Selwa, who has borne 12 children and had three survive, and of Samira, who has spent most of her adult life in love with her best friend’s husband.” The fictional American student mirrors Baugh’s own experience – she spent her junior year abroad studying at the American University in Cairo, where she rowed crew for AUC on the Nile and met her future husband, a member of the Egyptian National Crew team. Carolyn spoke about her book to altmuslimah’s Asma Uddin and Sarah Rashid.

![]() I can’t help but notice the parallels between your biography and that of the novel’s main character – both of you are American women spending a year studying in Cairo. To what extent is the character representative of yourself?

I can’t help but notice the parallels between your biography and that of the novel’s main character – both of you are American women spending a year studying in Cairo. To what extent is the character representative of yourself?

Carolyn Baugh: Well, it’s definitely my story in some ways. Certainly almost all aspects of the journal-type entries that exist between the stories of the women are autobiographical. My Cairo Journal. I consciously took out a lot of extra things about myself and my own experiences that I thought were mucking up the focus, and I purposely stripped her of a name. At some point I decided that I was consciously trying not to talk about me. I wanted the narrator to be a listener, maybe a better listener than I was when I was there, and when I’ve been there subsequently. And I wanted it to be crystal clear that she had a lot to learn; it was important that she be a liminal character, exploring borders. But even when I talk about the book, I sometimes say “me” when I mean to say “her.”

![]() Relatedly, the discussion questions at the back of the book note: “The narrator is there to learn a language not her own. Discuss the relationship between learning the language of another culture and cultural understanding.” Can you tell us a little about your personal experience learning Arabic and your understanding of the Arab culture?

Relatedly, the discussion questions at the back of the book note: “The narrator is there to learn a language not her own. Discuss the relationship between learning the language of another culture and cultural understanding.” Can you tell us a little about your personal experience learning Arabic and your understanding of the Arab culture?

Well, I have a “do-not-try-this-at-home” experience of learning Arabic– meaning, you can definitely learn Arabic without being married to an Egyptian for 17 years. But my husband’s initially-nonexistent English skills forced my Arabic to new heights!

I had studied two years in college, then a summer at Middlebury, so I had just the right foundations to build on. And then once I got to Egypt, everything started clicking into place. I absolutely recommend Middlebury, and I have to say that having some idea about how colloquial Arabic works is essential before trying to live in the host country– which I also think everyone should do who is serious about learning Arabic. Arabic is very beautiful and expressive, and it requires a lot of …cultural attention. I mean, the little things make a big difference when it comes to interaction with actual Arabic speakers. So if you are a guest in someone’s house, and they say, “You’ve brought us light,” then you get a lot more points if you know that the correct response is, “It’s your light!” or, “Egypt’s people are her source of light!” It’s very much a two-part harmony. People were overwhelmingly happy when I started being able to “sing along,” as it were. And I believe it made them more willing to sort of adopt me.

![]() Your novel discusses the stories of multiple generations of women. It seems that the deeper you go into history, the more oppressive the woman’s experience. Do you think that with time, Egyptian women are being given more choice in who they will marry, and more freedom within their marriages? If so, what is contributing to this trend?

Your novel discusses the stories of multiple generations of women. It seems that the deeper you go into history, the more oppressive the woman’s experience. Do you think that with time, Egyptian women are being given more choice in who they will marry, and more freedom within their marriages? If so, what is contributing to this trend?

Look, I think it’s undeniable that in any society, the better educated women become, the more they are able to claim their rights to self-possession. Interestingly the Arabic from the main hadith relating to consent in marriage, “The unmarried woman has more right to herself (al-ayyim aḥaqq binafsihā) than her marriage guardian.” Muslim women have the right to self-possession, but a lot of us don’t know it. (Yet.) The same goes, of course, for rights within marriage. The more we know, the better off we are.

Education is key, not just literacy, but actual Islamic literacy, which we need as close to home as Philly. Most Muslim women don’t know they can stipulate very specific conditions in their marriage contracts that prevent everything from a husband’s second marriage to him moving her far away from her family, or conditions that guarantee her right to work outside the home or continue her higher education.

In Egypt, well, it’s tough to generalize, right— I’ve seen in my own extended family-by-marriage that several cousins have been rejecting grooms left and right. My one cousin, who’s nearing thirty, won’t even consider beginning the steps of an “arranged” marriage, because a) she is completely unconvinced that anyone is happy in their marriages, much less in ones that are engineered, and b) she’s waiting for a love story. Her family has decided not to pressure her, and I hope they give her her space.

![]() Samira’s story adds an interesting dimension to the whole novel, speaking as it does about a love that is deep and profoundly real. Her story is the realization of that fantastical notion of romantic love that everyone knows about but few experience. Of course, her experience is somewhat inhibited because of her and Hasan’s moral obligations to their families, but she does indulge quite a bit. What were you trying to do with this story?

Samira’s story adds an interesting dimension to the whole novel, speaking as it does about a love that is deep and profoundly real. Her story is the realization of that fantastical notion of romantic love that everyone knows about but few experience. Of course, her experience is somewhat inhibited because of her and Hasan’s moral obligations to their families, but she does indulge quite a bit. What were you trying to do with this story?

Okay, so Samira’s story is either loved or hated by people who read it. I was asking myself a few different things. One, it’s an exploration of the concept of zinā. Zinā is punishable in Islamic law if there are four eyewitnesses to penetration, so it has to be very public and very graphic in order to get caught. Which means that, literally, we’re being told to cover it the heck up. It’s still a major sin of course, but I wanted to think through a couple who actually succeeded in covering it up, keeping it out of the public eye so that the sort of rupture in the fabric of society that adultery causes (the break-up of marriages, the scandal, etc) wouldn’t happen in this case. I found that Samira and Hasan could get their moments of joy in my constructed safe space, but that they were always suffering outside of that space, living half-lives, not being able to be truly present in the lives of their families, and in the end having nothing to show for it, not even a picture. So I was also exploring the idea of repentance-through-suffering, or that hadith that tells us that every pin-prick of pain in this lifetime is the erasing of a sin.

My high school English teacher wrote me and told me it was the one story she didn’t like because she was sure they would have gotten caught. I laughed out loud when I read that, and remembered a story my mother-in-law had told me of her little clique of retired friends and their day at the beach. They observed a young woman and her significant other (boyfriend? Fiance?) sitting together on the sand, and she was leaning up against his knees. And the older women were so outraged by this display that one of them, Umm Mediha, went after them with her cane, shouting, “Girl, don’t you have a mother??!!” The two dispersed.

My mother-in-law was chuckling as she recounted this, and I was thinking that there’s a whole story in a group of older women who would begrudge that space to someone who is young and happy. I don’t know; it made me sad. So yah, my teacher was right. Samira and Hasan would have gotten caught. The neighbors would probably have turned them in.

![]() Afkar’s story was, for me, the most heartbreaking. Her father cared so much for her that he felt obliged to marry her off to her love. Her husband, in turn, ended up being deeply insecure and both mentally and physically abusive. When compared to the other stories, it seemed like maybe the arranged marriage route may be safer than a “love marriage”, or at least equally unpredictable when it comes to finding the right match. Did you intend to make that comparison?

Afkar’s story was, for me, the most heartbreaking. Her father cared so much for her that he felt obliged to marry her off to her love. Her husband, in turn, ended up being deeply insecure and both mentally and physically abusive. When compared to the other stories, it seemed like maybe the arranged marriage route may be safer than a “love marriage”, or at least equally unpredictable when it comes to finding the right match. Did you intend to make that comparison?

Okay, exactly and confessionally, what happened with that story was the following: It was the next day after my sister-in-law was married, in a marriage that shook me up really badly because I loved her so much and I was so sure she was settling, that I was drinking tea with a former Arabic language professor who chided me for my assumptions. She said something about having married the most handsome man on the planet, who women would flirt with as he walked down the street, and because he treated her so badly she came to see him as Satan, whereas there was every possibility that my sister-in-law would come to see her husband as a prince.

I didn’t get nosy with my Arabic professor, so I was left to invent a whole world in which that could happen. And I didn’t have to look far, because I kept encountering stories about the toll that economics and economic realities had taken on otherwise happy marriages. So Afkar’s was a composite of many different stories. And it was also a way of countering, as you said, the arranged marriage notion. Perhaps clumsily. But my sister-in-law has always teased me when I’ve been in a rough patch in my marriage. “I can always blame my mother. You, you only have yourself to blame!”

![]() Your area of academic study is gender and Islamic law. In Samira’s story, you mentioned that if Samira had chosen to get a divorce from her husband, Egyptian law would have given him custody of her son. To what extent is this rooted in Islamic law? Is it something that should and could be reformed with a scriptural reinterpretation?

Your area of academic study is gender and Islamic law. In Samira’s story, you mentioned that if Samira had chosen to get a divorce from her husband, Egyptian law would have given him custody of her son. To what extent is this rooted in Islamic law? Is it something that should and could be reformed with a scriptural reinterpretation?

Oh, wow, there is no area of family law in any Muslim country today that doesn’t need reform. But the problem here is remarriage. Islamic law gives custody of the children to the father if a mother remarries, based on the hadith [variously related, through different isnads, some narratives centering around the wife of ‘Umar ibn al-Khattab] that a woman went to the Prophet to complain that not only was her husband divorcing her, but he wanted to take her son, “whom she had sheltered in her womb, and nursed from her breast.” The Prophet replies, “You are more deserving of him as long as you don’t remarry.”

As we know, though, Islamic Law and the laws of Muslim-majority countries are not usually the same thing. After a certain age (this varies widely according to definitions of maturity and puberty, and is tending to get later and later) in some Muslim countries, the husband can get sole custody of children, especially boys. I have heard heartbreaking stories in Egypt and elsewhere. It wasn’t until 2005 that parliament amended the child custody laws in Egypt; it was on the books that at the age of 10 for boys and 12 for girls, children transferred from the mother’s to the father’s care. Now the age is 15, and children are asked which parent they prefer. (But now the fathers are complaining that this divests them of their rights…)

Again, the better educated women are, the better they are able to fight for their rights as mothers. I cannot encourage women enough to become religious scholars, put their Arabic to use or attain the Arabic they need to be able to counter the overwhelmingly patriarchal interpretations of laws pertaining to women; as long as the task of interpreting the laws is left to men, there is no reason to expect more than the bare minimum, if that. Once you start digging, there is so much space to be found; it can be very exhilarating. And there is a strong history of results: the reform in Egypt’s laws to allow woman-initiated divorce (khul’) didn’t happen without major debates over the sources; and this was less than ten years ago. Only last year, the law preventing female circumcision was finally passed. Women played huge roles in these reforms; health care workers, most of them women, came out in droves protesting against circumcision after a thirteen year old girl died.. Not everyone can be a scholar, but we need them really badly. And beyond (and alongside) this, we just need concern and activism. Activism based on knowledge! Islamic activism is knowledge-based– A lot of ʿamal without ʿilm can be self-defeating.

Would I advocate for across the board women’s custody of children after remarriage? Islamically and personally I would hesitate to say yes. You know, what’s difficult with law is that people just aren’t cut from some mold, with everyone having the same experiences. What IS special about Islamic Law as a theoretical construct (i.e., not as is practiced in countries that have attempted black and white codification) is that it could be very personal, with the mufti knowing the particulars of a case and responding as needed, his decisions being shaped by the sources. I certainly wouldn’t claim to have read all the relevant sources, but I would love to work on this subject. I do know that there are a million early narratives about marriage and divorce, and women were encouraged to remarry, as the Qur’an suggests in 2:232. Still, the intent of the law, or the reasoning behind keeping mothers from remarrying is undeniably first as a deterrent to keep marriages together, second to prevent situations where a stepfather is living in a house with a stepdaughter and could abuse her sexually, and finally of course to keep the father in the picture as much as possible, for the psychological well-being of his own children.

![]() Throughout the novel, you refer to the Evil Eye as an explanation for a number of occurrences and as a constant warning to the women in their stories. The Evil Eye seems to have a very real and powerful presence in the book, beyond mere superstition. And in many cases, it was used as a form of oppression from one woman onto another. For instance, Selwa’s neighbor, who had a sick child, gave a terrifying stare to Selwa and her healthy child, and immediately thereafter, Selwa’s child became sick and died. Can you explain why you gave so much prominence to the Evil Eye and what it says about female-female oppression?

Throughout the novel, you refer to the Evil Eye as an explanation for a number of occurrences and as a constant warning to the women in their stories. The Evil Eye seems to have a very real and powerful presence in the book, beyond mere superstition. And in many cases, it was used as a form of oppression from one woman onto another. For instance, Selwa’s neighbor, who had a sick child, gave a terrifying stare to Selwa and her healthy child, and immediately thereafter, Selwa’s child became sick and died. Can you explain why you gave so much prominence to the Evil Eye and what it says about female-female oppression?

Lack of education is always, I think, the main culprit in female-female oppression. (Which is why so many women perpetuate customs like genital mutilation.) But the Evil Eye is huge in Egypt, and you find even the most educated people sometimes paying a bit of verbal homage to the eye, or wearing charms, putting up palm prints– my husband and his uncle did that straight off at their restaurant. I have an aunt by marriage who is so terrified that someone will cast the Eye on her beautiful daughters that she can barely even speak about them in public. And it’s not just a Muslim phenomenon. If you watch the film “Arranged,” you can see a scene where the young Jewish woman (also trying to find a spouse) puts on an amulet against the Evil Eye. It’s a very Mediterranean thing, and it really interests me how it is shared across many cultures. And look, if we read the early exegesis of Surat al-Falaq, it’s very clear that even the early Muslims were very convinced of the power of humans to cast the eye of envy (ʿayn al-ḥasad). Tabari, for example, was just passing along early opinions when he relates Tawūs as saying that, “the Eye is true.” There was even a custom that anyone who believed himself struck by the Eye would go and ask the person who cast the Eye to do ghusl to alleviate the effects. So, I think we have a case where, Quranically, there is an acknowledgment of the dangers of envy, and the need to insist on power belonging only to God. What interests me the most today, though, is the way that some believing Muslims can cede such immense power to humans; it strikes me as shirk. But that doesn’t mean I stalk off when my mother-in-law comes around with her incense pot!

![]() There was an interesting conversation that occurred between the main character and her roommate Meg. They were discussing female genital mutilation (FGM). The main character says she doesn’t understand how a mother could do that to her daughters, and Meg responds by giving examples of how Western women do absurd things for beauty, men, etc. With Meg’s response, the conversation ends and the scene changes. Why did you choose to compare FGM with a woman’s voluntary choice to dress scantily? FGM forces a woman to live with the consequences of something she had no choice over, and the latter is a choice a woman makes for herself; as oppressive as we want to say it is, it’s still her choice. Can you explain what you intended to convey through that conversation?

There was an interesting conversation that occurred between the main character and her roommate Meg. They were discussing female genital mutilation (FGM). The main character says she doesn’t understand how a mother could do that to her daughters, and Meg responds by giving examples of how Western women do absurd things for beauty, men, etc. With Meg’s response, the conversation ends and the scene changes. Why did you choose to compare FGM with a woman’s voluntary choice to dress scantily? FGM forces a woman to live with the consequences of something she had no choice over, and the latter is a choice a woman makes for herself; as oppressive as we want to say it is, it’s still her choice. Can you explain what you intended to convey through that conversation?

Well, I believe strongly that many women in our society are so locked into the conceptions about body beauty that are dumped on them (from Barbie right on down) that the choice becomes no choice. And it’s peer pressure, and female-female oppression as much as anything related in my book. I wasn’t talking about scanty dress as much as actual surgery and actual bodily harm that women inflict upon themselves, from bulimia to liposuction to breast implants. And when women vie with each other in these areas, who can be the thinnest and sexiest, who can exert the most physical-attraction power over men– or over each other!–then I find them complicit. God, and the loss of self (where’s the self-possession?) that occurs when a woman finds herself to be “no woman” because she does not look a certain way, “no human”…. Nothing. What a huge loss, when the intellect and the soul are just itching to be developed and let loose on the world! I believe that when a woman is evaluated only on how she exists in relation to men (East, West, North, South, Muslim, non-Muslim), then we have a problem. And I think it’s a shared problem for all women, even if the actual manifestations of it look different from place to place.

![]() The novel in many ways is not just about the women’s stories, but also about the men they are related to. Your book offers diverse types of male characters – some loving, some brutal. Some of these men challenge the stereotypes; others fit perfectly within them. Was your intent with the book to give voice to Muslim men in addition to Muslim women? If so, to what extent?

The novel in many ways is not just about the women’s stories, but also about the men they are related to. Your book offers diverse types of male characters – some loving, some brutal. Some of these men challenge the stereotypes; others fit perfectly within them. Was your intent with the book to give voice to Muslim men in addition to Muslim women? If so, to what extent?

Well, it’s as simple as portraying some of the men I came to know, or aspects of them, along the way; and I definitely wasn’t sitting down to write anymore stereotypes. The story of the father who prevented his daughter’s circumcision is a true one, and it deeply impressed me that it was the man who stood up for his daughter instead of the mother. And I needed a lover of literature, even though I didn’t know any personally, because I know they’re out there, and because those who have been writing beautiful Arabic poetry for centuries did not and do not exist in a vacuum. And for Huda, I needed her husband to be a good and gentle man, like some of my sweetly hopeful young cousins who’d grown up by the time I got to writing, and were starting to think about brides, while being very poor and very awkward around women. My editor actually asked me to make Ehab a wife-beater! I refused. I’d only heard stories about one of those, and that was plenty.

![]() How does the main character’s cross-cultural perspective mature along with the stories she hears? What is her journey as she learns about these women? Her voice is soft throughout the book as the spotlight is put on the Egyptian women, but you can’t help but wonder about her. She is a foreigner immersed in a different culture. She is the character the average non-Muslim reader can relate to most, yet she is so quiet in the book. By making her thus, are you advocating a more objective, less judgmental approach toward learning about another culture? Are you creating a contrast to the usual Western feminist approach about “saving” Eastern women without having a real understanding about their context?

How does the main character’s cross-cultural perspective mature along with the stories she hears? What is her journey as she learns about these women? Her voice is soft throughout the book as the spotlight is put on the Egyptian women, but you can’t help but wonder about her. She is a foreigner immersed in a different culture. She is the character the average non-Muslim reader can relate to most, yet she is so quiet in the book. By making her thus, are you advocating a more objective, less judgmental approach toward learning about another culture? Are you creating a contrast to the usual Western feminist approach about “saving” Eastern women without having a real understanding about their context?

Yes, definitely: in fact, I rewrote it a lot and took out a lot of her blabbering. I started feeling like everything she was saying was judgmental, so I just shut her the heck up as much as I could. I didn’t want her assumptions to distract, and I didn’t want her to be out to “save” anybody.

But it’s still me writing, and I have to confess there were some ambiguities for me, and because writing is a process by which I sort things out, I was using it as a way to try to understand how there are women I love so deeply in Egypt, family members and friends, with whom I can feel so close, and yet suddenly feel so different that it’s like we’re looking at each other from across a chasm. So I wanted to work through this, but I knew in order to do it that I had to lay myself open to listening to where these women are coming from. There is little growth and development for the narrator, no major arc, but I hope that it’s clear by the time you find her sitting on Huda’s balcony that she feels that the two of them flow along on the same deep river.

![]() At the end of the book, you discuss misconceptions about Islamic Law and women. You say that women’s oppression is not limited to Muslim societies and Islam, and in doing so, you contextualize your book with a larger conversation about patriarchy and tradition. Your final words are, “…all women negotiate a mixture of tradition and patriarchal culture. Some women emerge from their experiences more gracefully than others. This book is my ode to that grace.” Why did you decide to include this note? Did you feel that without it, readers might not make the connection between the suffering of these women and the suffering of all women, deciding instead to view Egyptian or Muslim society in a vacuum, as people tend to do these days?

At the end of the book, you discuss misconceptions about Islamic Law and women. You say that women’s oppression is not limited to Muslim societies and Islam, and in doing so, you contextualize your book with a larger conversation about patriarchy and tradition. Your final words are, “…all women negotiate a mixture of tradition and patriarchal culture. Some women emerge from their experiences more gracefully than others. This book is my ode to that grace.” Why did you decide to include this note? Did you feel that without it, readers might not make the connection between the suffering of these women and the suffering of all women, deciding instead to view Egyptian or Muslim society in a vacuum, as people tend to do these days?

Well, look, I wrote this book before 9-11, and before I went to grad school; its focus was geared entirely toward exploring shared spaces between women. And like I’ve said, I was wanting to sort through some personal confusion about relationships with women in my family-by-marriage, and a desire to try to understand what motivates and shapes them. In some ways, with the urgency of the present situation of anti-Islamic attitudes worldwide, I worry that the book is a little too self-indulgent. It’s like, Maybe I should have thrown my hat into the non-fiction what-Islam-really-is genre – we’ve gotta write for the Cause!

But the book is fiction based on a landscape of reality. The book conveys my very real Muslim-woman-frustration that things just aren’t generally better, and that culture has such a choke-hold on so many of our sisters.

Needless to say, though, I wasn’t trying to come up with something that can work as ammunition against Islam for those who function on hatred and fear. So, yes, I wanted to insist, at the end, that there’s more to the story than this. And I wanted to make sure that, before anyone starts feeling smug about “Western freedoms,” we’ve got to acknowledge that we all have a long way to go.

Asma Uddin is Editor-in-Chief of Altmuslimah. Sarah Rashid is a student of fashion design.