In her latest piece for Aeon, Rafia Zakaria asks:

Why do empires care so much about women’s clothes?

In 1820, in the Indian city of Benares, an English Baptist missionary named Smith helped to save a woman from the Hindu practice of sati, the burning of widows. He described the scene: ‘As soon as the flames touched her, she jumped off the pile. Immediately the Brahmins seized her, in order to put her again into the flames: she exclaimed, “Do not murder me! I don’t wish to be burnt!” The Company Officers being present, she was brought home safely.’ A London magazine reported the heroic efforts of Britain’s East India Company under the headline ‘A Woman Delivered’. If there was one thing 19th-century Europeans knew about India, it was probably sati.

Mr Smith’s 1820 account of valiant British men rescuing an Indian woman from her husband’s funeral pyre is one of many such contemporary reports. The East India Company had just become the effective governing authority of India. As a trading presence, it had been uninterested in culture. As a ruling presence, it set out to reform the barbaric local customs.

More recently, it is Afghan women who’ve needed the Anglo-American empire to deliver them. In 2002, a coalition of Western women’s organisations sent an open letter to the US President George W Bush asking him to ‘to take emergency action to save the lives and secure the future of Afghan women’. Its signatories included Eleanor Smeal, President of the Feminist Majority Foundation in Virginia, together with other notable feminists such as Gloria Steinem, Eve Ensler, Meryl Streep and Susan Sarandon. US women overwhelmingly support the war, they noted, because it will ‘liberate Afghan women from abuse and oppression’.

…

So why the particular focus on saving native women?

Do women, their freedom, their clothes and their marriages provide some crucial avenue into establishing hegemony, a method of representing the foreign invaders as good? The most compelling reason for this enquiry is that South Asian and Afghan feminisms are tainted by an imagined complicity with colonialism and imperialism. Making explicit just how aspects of women’s lives – their clothes and marriages – have been put into the service of Anglo-American imperial projects of domination, and how little these projects have had to do with those actual women, is a step towards lifting the weight of imperial complicity on Afghan feminism.

Read more.

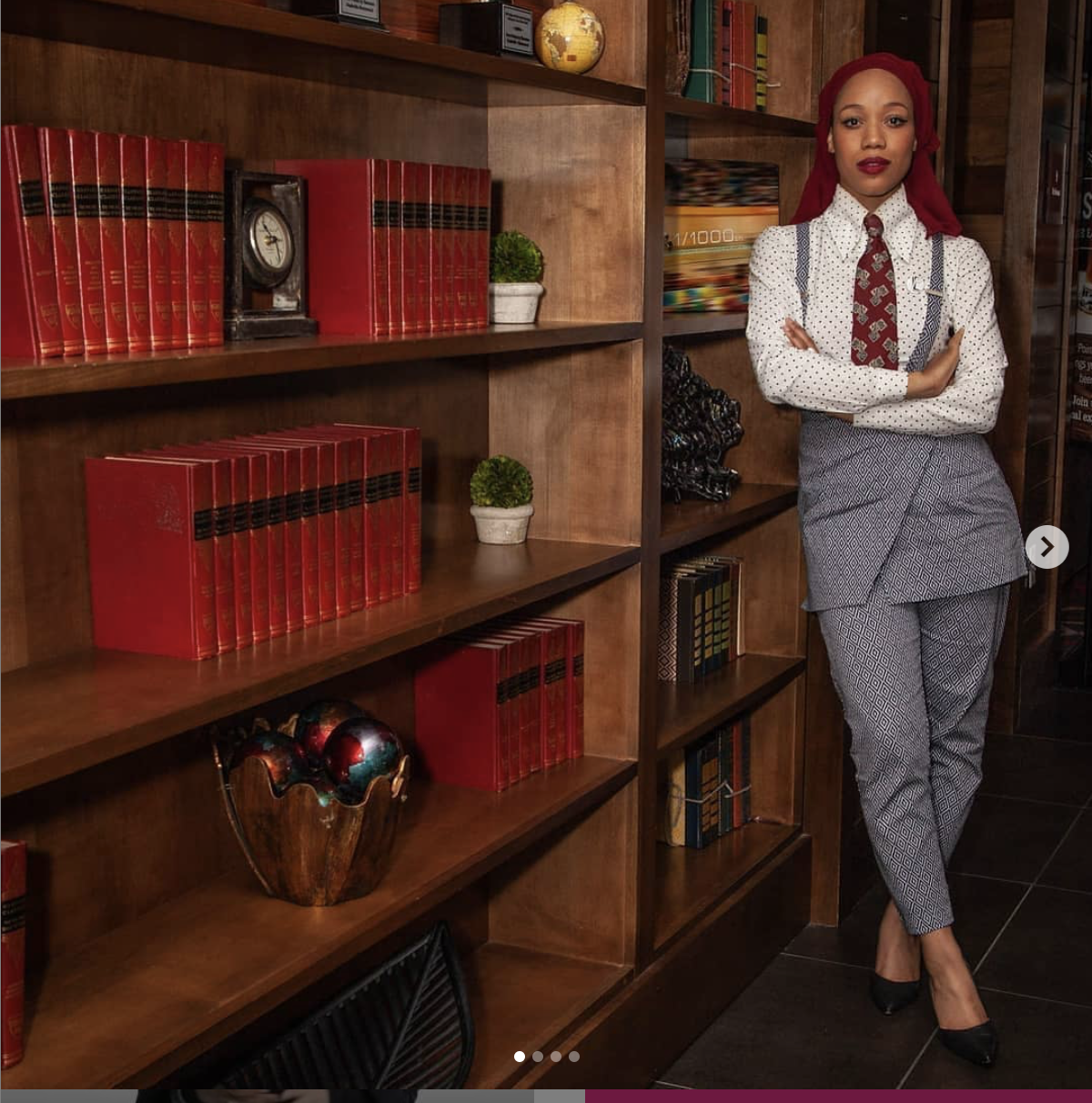

Photo: Institute for Money, Technology and Financial Inclusion

1 Comment