In 2012, Ayesha Mattu and Nura Maznavi released Love, InshAllah – The Secret Love Lives of American Muslim Women, hoping to spur a “more compassionate and respectful intra-faith dialogue” about relationship complexities within the Muslim community.

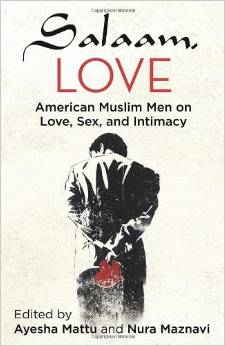

Despite the success of their first release, Mattu and Maznavi never considered assembling a male counterpart to Love, InshAllah. They admit in the introduction to Salaam, Love – American Muslim Men on Love, Sex and Intimacy that even after receiving such requests, they “dismissed the inquiries with a laugh. “Please! Guys don’t talk about … (their feelings).” The sheer quantity of inquiries, however, soon changed their mind, and so we have a collection of 22 stories to review.

While I will not call Salaam, Love a must-read, it is certainly a good-read – though not from cover to cover (more on that later). While close friends do let their guard down in private, the written word might very well be the best medium for men to articulate the gamut of emotions expressed here. Frankly, I am unlikely to even tell my buddies that I am reviewing such a book, but I will confess to you the reader that it was enjoyable, and often powerful, to read an honest book on these sometimes taboo topics.

Arsalan Ahmed introduces us to the classic “emotional cold war” between mother and son. We learn an important lesson for those struggling with a mother’s obstinacy to marital decisions – that it can be made to wither when push comes to shove. However, we are also left to reflect on the power of a mother’s curse.

As would be expected in 2014, openly gay Muslims find space in this anthology as well. A. Khan describes how the emotional strain of a compartmentalized identity in the wake of coming out drove him to seek refuge in hook-up culture. A chance encounter with a man who promptly followed their hook-up session with the mid-day Muslim prayer puts Khan on the path to reconciling his piety and his sexuality.

Young men have much to learn from Yousef Turshani, who provides a template not only for supporting a woman’s career aspirations long-distance, but also how to stand up to a mother’s deeply loving, yet deeply unhealthy, attachment. The latter, in particular, is a topic that is difficult to address within the confines of Islamic adab (appropriate respectfulness), and Turshani’s ability to do so speaks to the usefulness of this anthology.

Alykhan Boolani highlights how “Terrified Immigrant Syndrome” can be an even more intense phenomenon in smaller Islamic sects, and how the ever present specter of community involvement stifles promising romantic connections. John Austin gets us rooting for him and his girlfriend, only to break our hearts as his is broken by the ugly racism which many African-American Muslims have faced from prospective immigrant in-laws.

Maher Reham provides the important perspective of someone who decides to pursue an extra-marital affair. We hear him talk through his moral dilemmas multiple times, both as a college student pushing the limits with his girlfriend, and later as a married man seeking outside comfort. Many could benefit from reading how sexual baggage from the past can create sizable barriers in a relationship, and how continued sexual validation requires an active effort after tying the knot.

The book ends with wrenching stories of helping a wife deal with aggressive illness -as Randy Nasson charts how the transition from lover to caregiver and back catches one by surprise. Alan Howard’s eight years of caring for his wife as she died from cancer touches on an important subject that – again, is difficult to broach with adab, but which must be shared because of all those who silently struggle – that of feeling anger towards God.

Not every story in this book was powerful – some were flat-out boring. Others should have been shorter. Others still hint at greater lessons that never quite materialize. Some essays contained references to masturbation and pornography that seemed forced and tangential to the main story, floating aimlessly within an essay.

While the diversity is generally admirable, I level the same complaint that I do against other such anthologies –the book lacks blue-collar, non-professional voices. In addition, while we need stories of Muslims finding peace despite defying communal norms, the book would be more balanced if a few authors with a more conservative bent made the cut as well.

One of the contributors notes, “Love, and wholeness, emerge in and from places where society says they aren’t supposed to.” Some would say that many of these stories also emerge from places Islam says they aren’t supposed to. For some, this book is more likely to produce an aneurism than an epiphany. But we have to remind ourselves, as the editors do early on, that no one has to accept any of the philosophies presented as Islam, but the individuals must be greeted and heard as members of the Ummah. I would particularly recommend this book to anyone who finds their local community stale and devoid of new and honest perspectives.

Abrar Qadir is an attorney in the Bay Area, California. He holds a B.A. from the University of California, Berkeley, and a J.D. from Georgetown University Law Center, and runs a regular blog at Punjabirefill.tumblr.com.